2+pic.1+ca.2(2 dbl. bcl.)1+cbn./2.3(3 is picc. tpt).1+btbn.0./4perc/1hp/pno/str

Premiered by Lynn Harrell, Cello soloist, with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Christoph Eschenbach conducting, 14-16 March 2013

Duration: 26 minutes

Live concert audio recording from World Premiere is available for archival purposes only and for private listening. If you would like to review the recording please Contact Augusta Read Thomas.

Augusta Read Thomas was born in Glen Cove, New York, on April 24, 1964, and lives in Chicago. Her Cello Concerto No. 3 was commissioned by the Boston Symphony Orchestra through the generous support from Mr. and Mrs. William G. Brown, with additional support from Catherine and Paul Buttenwieser, and from the New Works Fund established by the Massachusetts Cultural Council, a state agency. Thomas composed the concerto expressly with the BSO, cellist Lynn Harrell, and Symphony Hall in mind, starting work in January 2012 and finishing by October of that year. These are the first performances of the concerto.

In addition to the solo cello, Thomas's Cello Concerto No. 3 calls for two flutes and piccolo, oboe, English horn, two clarinets (second doubling bass clarinet), bassoon, contrabassoon, two horns, two trumpets in C, piccolo trumpet in B-flat, trombone, bass trombone, percussion (four players — I. glockenspiel, small, medium, and large triangles, wood blocks, low tom-toms; II. crotales, triangle, suspended cymbal, bongos; III. vibraphone, triangle, claves, congas, taiko drum; IV. marimba, tubular bells, finger cymbals, suspended cymbal, tenor drum, bass drum), harp, piano, celesta (optional but preferred), and strings. The piece is about thirty minutes long.

"Although my music is highly notated, precise, carefully structured, and soundly proportioned, and while musicians are elegantly working from a nuanced, specific text, I like it to have the feeling that it is organically being self-propelled — on the spot — as if we listeners are overhearing (capturing) an un-notated improvisation."

"Organic and at every level concerned with transformations and connections, my music is always leading me toward a fundamental goal: to try to compose a work in which every musical parameter is allied holistically."

— Augusta Read Thomas

For Augusta Read Thomas, music is a physical thing. This relates, directly, to her awareness of the physical process of performance for a given instrument — a cellist and a bassoonist do things very differently to produce the same pitch, for example — but also to the experience of the listener. The listener, reacting to music, is swept away in a brisk passage, or feels physically a big orchestral swell, or is becalmed by a sustained harmony or shifting pattern. Thomas mirrors the experiences of the instrumentalist, the conductor, the singer, and the listener all while she composes, standing at one of her tall drafting tables. She sings, claps, plays piano, dances, embodying the physical presence of the music she's writing. That activity is fundamentally transmitted through the notes on the page to the minds and bodies of the players and thus finally to the audience. She plucks one end of that conceptual thread, and its vibrations ultimately catch in the ears of the listener.

Thomas's work titles suggest a key to this aesthetic philosophy. She prefers titles with evocative significance, such as Orbital Beacons (her concerto for orchestra); Astral Canticle for flute, violin, and orchestra, or Helios Choros ("Sun God Dancers") for orchestra, to name just a few. Celestial imagery, the terrestrial sky, the ocean, and, perhaps most importantly, dance hint at the composer's preoccupation with a kind of cosmic order, along with an openness to mystery and contemplation and a grounding in the physical, bodily origins of music.

With its incredible variety of sonic possibilities, the orchestra is naturally the ensemble that best fits Thomas's acoustic imagination. Her experience writing for orchestra is remarkably vast compared to that of most composers. She was composer-in-residence with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra for ten years, composing nine works for that ensemble (including Aurora, In My Sky at Twilight, and Orbital Beacons) and working closely with both Daniel Barenboim and Pierre Boulez. One of her earliest and most ardent champions was the great cellist and conductor Mstislav Rostropovich, who commissioned her one-act opera Ligeia for the Evian Festival; and as conductor of the National Symphony Orchestra, he led the premieres of her symphony Air and Angels (1992) and the orchestral work Galaxy Dances (2004). She wrote her short cello and orchestra work Chanson for Rostropovich in celebration of his 70th birthday, and that piece (since withdrawn from her catalog) was premiered by the cellist with the Boston Symphony Orchestra led by Seiji Ozawa in 1997. In addition to that piece, the BSO has performed another of Thomas's orchestral works: her Helios Choros II, co-commissioned by the BSO, is the middle part of a big orchestral triptych lasting some three-quarters of an hour. The BSO gave its American premiere in November 2009. She has also written for a number of other U.S. and European ensembles, and has heard her music performed by still more. On March 17, 2013, her orchestral piece Harvest Drum receives its premiere by the Symphony Orchestra of the National Centre for the Performing Arts in Beijing, China, a culmination of the composer's residence among China's Miao community in 2011. Next week a mini-festival celebrating her music takes place at East Carolina University, and later this season her orchestral work Aureole, commissioned by DePaul University for its centennial, will be premiered in Chicago's Orchestra Hall.

Christoph Eschenbach, who leads this week's concerts, is another conductor who has championed Augusta Read Thomas's orchestral music, with the National Symphony Orchestra, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Philadelphia Orchestra, Orchestre de Paris, and the North German Radio Symphony Orchestra in Hamburg. For that orchestra she composed Chanting to Paradise, for soprano solo, mixed chorus, and orchestra, premiered under Eschenbach's direction in 2002. In 2011 he led the National Symphony Orchestra and soloist Jennifer Koh in the American premiere of her Violin Concerto No. 3: "Juggler in Paradise", also commissioned by Bill and Solange Brown.

As prolific as she has been — she has published over a hundred works — Thomas has touched on every other genre from solo pieces to opera, frequently working on very different kinds of pieces in quick succession. This changing perspective has helped keep each new piece and approach interesting and fresh. She spends most of her time composing, of course, but has maintained a well-rounded musical life as a curator and teacher as well. She created the Chicago Symphony Orchestra's MusicNow series, and was director of the 2009 Festival of Contemporary Music at Tanglewood, where she has also served as a faculty member on many occasions (having been a Tanglewood Fellow herself in 1989). She was the youngest tenured professor in the history of the Eastman School of Music, and has also taught at the Aspen Music Festival and Northwestern University. She is now the sixteenth University Professor (and one of five currently) in the history of the University of Chicago. Believing strongly in musical citizenship, she has also served as chairperson of the board of the American Music Center and serves on several other boards. In May 2009 she was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters, which cited "an impressive body of works [embodying] unbridled passion and fierce poetry."

Thomas has had the good fortune to be able to create several large-scale works in the same genre, for example three violin concertos, two trombone concertos, and, now, three cello concertos — an unusual circumstance for a contemporary composer (or for that matter a composer of any era after the Classical period). She wrote her first cello concerto, Vigil, in 1990 for the Cleveland Chamber Symphony and soloist Norman Fischer (a longtime Tanglewood faculty member and member of the Concord String Quartet). Her second, Ritual Incantations, was for Emerson String Quartet cellist David Finckel, who premiered it with the Aspen Music Festival Chamber Orchestra in 1999. Both were around twelve minutes long; the new concerto is a much bigger piece in every way.

The origin of the concerto can in part be traced to Thomas's patron Bill Brown's enthusiasm for her Violin Concerto No. 3 following Frank Peter Zimmermann's Paris premiere of that piece in 2009. Brown ultimately became one of the supporters of the Boston Symphony Orchestra's commission for the present work. After it was decided that Lynn Harrell was to be the soloist for this work, Thomas — who had not yet met the cellist — listened to as many of his recordings as possible in order to incorporate his particular felicities as a performer into her piece. (Two techniques tailored here for Harrell are pizzicato — plucking rather than bowing the strings — and spiccato, a fast, bouncing bow.) Having known many of the musicians of the Boston Symphony Orchestra for years, and having worked with and heard the orchestra before, Thomas approached the orchestration with the qualities of the BSO in mind as well.

About her new piece, Augusta Read Thomas writes:

"Numerous ways of looking at lyrical" was an image in ear and mind as I composed this concerto for Lynn Harrell. Listening to many of his performances and recordings, I love the way Lynn makes his cello sing at all times and treasure the way he is able to capture the deepest characters in music and elucidate them vividly and radiantly to his listeners. Across several colorful, contrasting sections (performed without pause), the soloist inspires and illuminates every aspect of the music; the orchestra listens and adds its own voice(s). The inventive soloist serves as protagonist as well as a fulcrum point on and around which the orchestra's musical-force-fields rotate, bloom, rise, interject, and proliferate.

One might describe Legend of the Phoenix as "Scenes with Arias" with the solo cello as a singing storyteller. Shaped in one long-reaching, continuous arch, the energy flow is often activated by the soloist, who is at the "philosophic center," beckoning, caressing, and summoning the music's chain of outgrowths.

With sparkling, radiant, and capriciously witty atmospheres that celebrate the soloist and orchestra, this concerto is optimistic, clean, colorful, bright, sunny. There exists a wide and spontaneous variety of characters, including: triumphant, in-flight, ever-renewing of energy, graceful, majestic, spacious, pure and clean, playful, spry, jazzy, lively, rhythmic, ever-rising, resonant, and elegantly vibrant....

As with most of Thomas's pieces, the subtitle Legend of the Phoenix indicates not a specific narrative but a jumping-off place for the imagination, with the phoenix's mystical origin providing first of all an atmosphere of wonder. Although one is tempted to equate the soloist with the bird, that connection is far too concrete. Nonetheless the cello is the originator of a line, a focal thread, that winds its way through the entire concerto, changing character as it goes and expanding into the orchestral roles. The orchestra itself, though not small, is not Mahlerian: the goal is a certain range of clarity and color, not overwhelming power. Even so, the orchestra has material that is its own, giving it a role equal to that of the soloist rather than that of mere accompanist or imitator.

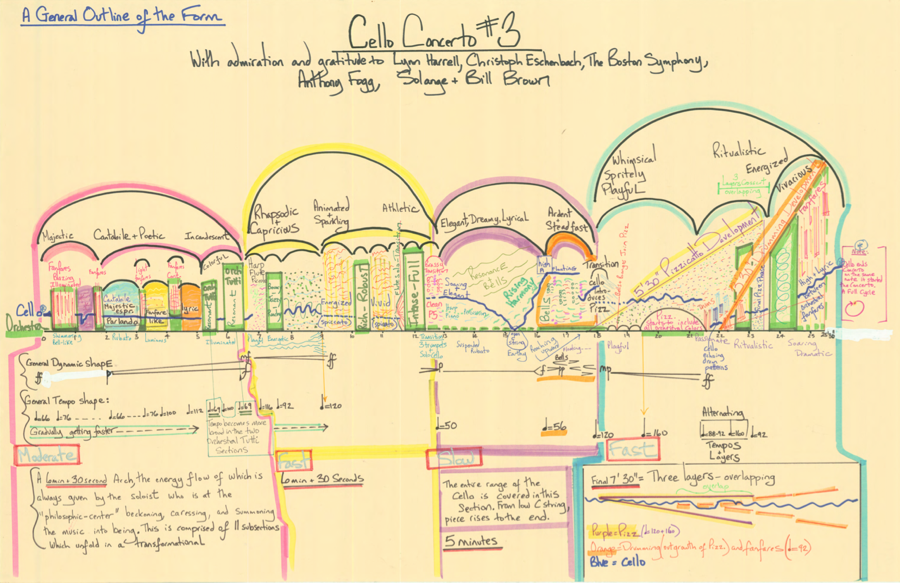

In legend, the phoenix dies in fire and is resurrected from its own ashes, a cycle that reflects the continual change and re-emergence of musical energy in the concerto's many episodes, on several different levels. That narrative of rebirth, hope, and change also informs the character of the music. The largest cycle is the arc of the whole piece, which begins with a determined A in the solo part and ends, full-cycle, on the same note. As one can see in the colorful "map" Thomas created for the piece (see page XX), the one-movement work has several evident subsections of changing character, and within those can be heard smaller transformations, and so on down to shifts of greater subtlety that take place on a several-measure level. Thomas marks these (as implied in her note above) with new characterizations for the orchestra, such as the opening's "Majestic; blazing; illuminated" to describe the bright fanfares in the orchestra, "Poetic and ardent" a little later, followed very quickly by "Rhapsodic, vivacious, capricious" to indicate the jazzy passage that follows the primarily lyrical first big section. Thomas's reference to the "singing" quality of Lynn Harrell's cello playing is to be found not only in the sustained, cantabile ("singing") passages of the concerto but also in the bebop-like, rhythmically off-balance passages. For the first of these quick passages the composer suggests the soloist think of the vocal techniques of "parlando and scat" — parlando meaning speechlike, and scat referring to wordless improvisation in jazz singing.

Even as the music itself is in a state of constant transformation, we can discern connections among the recurrences of the fanfare figures, among episodes of broad, searching melodies or fast, rhythmic music. Very broadly speaking, the piece can be heard as slow-fast-slow-fast. The opening section features the solo cello in very rangy, singing lines, which are reinvented as the jazzy passage mentioned above (with a bit of duet with the harp). "Energetic and bouncy" brings a passage for orchestra alone for few measures. The big fast passage — with indicators like "Animated and sparkling" — amply features the soloist's spiccato technique. An exposed flute solo is a signpost for the next big character change, initially marked "Auroral," introducing primarily sustained, ethereal music. Here the soloist finally descends to the cello's lowest range, descending to the open C-string, before rising, "...as if floating to eternity..." in a series of high, sustained harmonics. The final big section is fast and energized, beginning with "Whimsical; sprightly; playful." Percussion play a large role here as a kind of expanding echo-chamber for the soloist's prevalent pizzicato. Eventually the percussion role grows to dominate the sonic texture, planting the seeds for the short bursts (remember the earlier fanfares?) sounding throughout the entire orchestra, like big-band hits. The cello's final sustained A pushes this energy beyond the orchestra's last bright shout.

— Robert Kirzinger

Robert Kirzinger, a composer and annotator, is Assistant Director of Program Publications of the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

© 2013 by Robert Kirzinger for the Boston Symphony Orchestra

Colin Anderson, Classical Source Detroit Symphony Orchestra/Hannu Lintu s Pohjola's Daughter & Shostakovich 5; Lynn Harrell plays Augusta Read Thomas's Legend of the Phoenix [live webcast] Orchestra Hall, Detroit, Michigan

"Augusta Read Thomas's Legend of the Phoenix (2012) is her Third Cello Concerto, commissioned by the Boston Symphony Orchestra. It's a great piece, from its striking opening with intense declamation from the soloist and the orchestra's brightest instruments issuing an urgent invitation that we should be involved in the music, which is lyrical, rhapsodic and has tremendous brass outbursts. Lynn Harrell played marvellously, with rich tone, spot-on intonation and palpable commitment. The orchestra is kept very busy, vivid and beguiling on its own terms, ravishing at times, with contributions from such as piccolo and harp that leap out of the texture, and with plentiful percussion that never seems like overkill.

"The idea of the Phoenix legend (the bird that lives for one-thousand years, makes its own pyre, leaps on it, and then emerges from the ashes for another millennium of existence) only came to the composer during the composition, so it is not story-specific, which is just as well as I was compelled by the musical invention and its development and didn't worry overmuch as to musical description, a continuous movement with plenty of variety, drama, eloquence and whimsy, a capricious score that easily sustained its (here) 28-minute duration through full-on dramatics and enchanted escapes. I loved it to bits!"

Jeremy Eichler, The Boston Globe

Subject of Death livens up part of CSO's performance

Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Daniel Barenboim conducting

Symphony Center, Chicago

"Opening the score of Augusta Read Thomas's Cello Concerto No. 3, which received its premiere Thursday night, one encounters something telling about this composer's approach before reading a single note. At the bottom of the list of percussion required for this ambitious 30-minute work, Thomas writes that extra care should be given to make sure "each of the [five] triangles has a slightly different 'pitch and color' from one another, so that each of them has a unique contribution to the overall sonic palette and so they blend elegantly with the crotales, glockenspiel, and finger cymbals."

"This attention to minute detail is a hallmark of Thomas's music and reflects the delicacy of imagination with which she constructs her sound worlds. That this new work, a BSO commission, also contains a vivid theatricality of gesture, a certain lightness of being, makes it particularly successful.

"Despite its subtitle "Legend of the Phoenix," the work has no explicit narrative but unfolds in a single 30-minute span that divides into coherent sections. The first is full of expansively songful cello writing, with the brass on occasion interjecting fractured, flash-mob fanfares, appearing from nowhere and disappearing nearly as fast. The solo writing eventually gathers speed and angularity and the rhythms grow more jazzy before the cello takes us into a hazier, dreamier landscape. There is a vibrant pizzicato section and some ruggedly expressive solo cadenzas in the final pages. The work comes full circle, ending as it began with a high blast from the cello.

"On Thursday night cellist Lynn Harrell gave an assured and virtuosic performance, rendering the score's more declarative moments with the same unflagging confidence he brings to Romantic solo repertoire. From the podium, Christoph Eschenbach, who has performed much of Thomas's music, drew out an alert and vivid performance. The crowd's reception went well beyond the polite applause sometimes given to new scores."

David Wright, Boston Classical Review "While winter clamped down outside Symphony Hall Thursday night, hopes of rebirth blazed inside as the Boston Symphony Orchestra premiered a fiery new cello concerto by Augusta Read Thomas.

"Thomas's skillful scoring allowed cellist Harrell to rise above it all, both literally (seated on a foot-high platform) and sonically. While he too played far up the fingerboard at times, his part fell mostly in the human-voice range that is natural to his instrument. Speech rhythms — choppy, thoughtful, urgent, voluble — predominated over long cantabile lines...The music kept its shimmering colors and optimistic outlook throughout, and yet offered so much to keep the ear engaged that, when Harrell, playing alone at the end, finally put the period on this long sentence, one was surprised that a half hour had passed.

"Although Thomas has said that the image of the phoenix — the mythical bird who died by fire and was reborn from its ashes — suggested itself as a title only after the music was composed, there is nevertheless some pointedly avian music in between the pyrotechnics, not just the usual chirps and twitters, but some charmingly bony, beaky dancing for the soloist with harp, wood blocks and tom-toms. And speaking of tom-toms, it is a small step from evoking fire in high percussion and brass to the fierce rhythms of big-band jazz at its hottest — a step that Thomas most gratifyingly took in this score.

Andrea Shea, 90.9 WBUR's 'The Artery'

"Over the past 15 years the Boston Symphony Orchestra has commissioned 40 original works, but only six were composed by women. That number rises to seven this week with the premiere of a major cello concerto at Symphony Hall...[Conductor Christoph Eschenbach] calls Read Thomas by the nickname 'Augustie' and gives his friend's cello concerto a big thumbs up. "It's a masterpiece, I think. As every piece I know of hers, she's just a great composer," Eschenbach said."

read the review

To purchase a map of CELLO CONCERTO #3, please visit the Online Store.

To obtain examination or performance material for any of

Augusta Read Thomas's works, please contact G. Schirmer Inc..