Picc.32E.H.3B.CL.2C.Bsn./4331/4 perc./timpani/harp/piano/strings

Commissioned and premiered by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Pierre Boulez conducting on 12 December 1996

Duration: 18 minutes

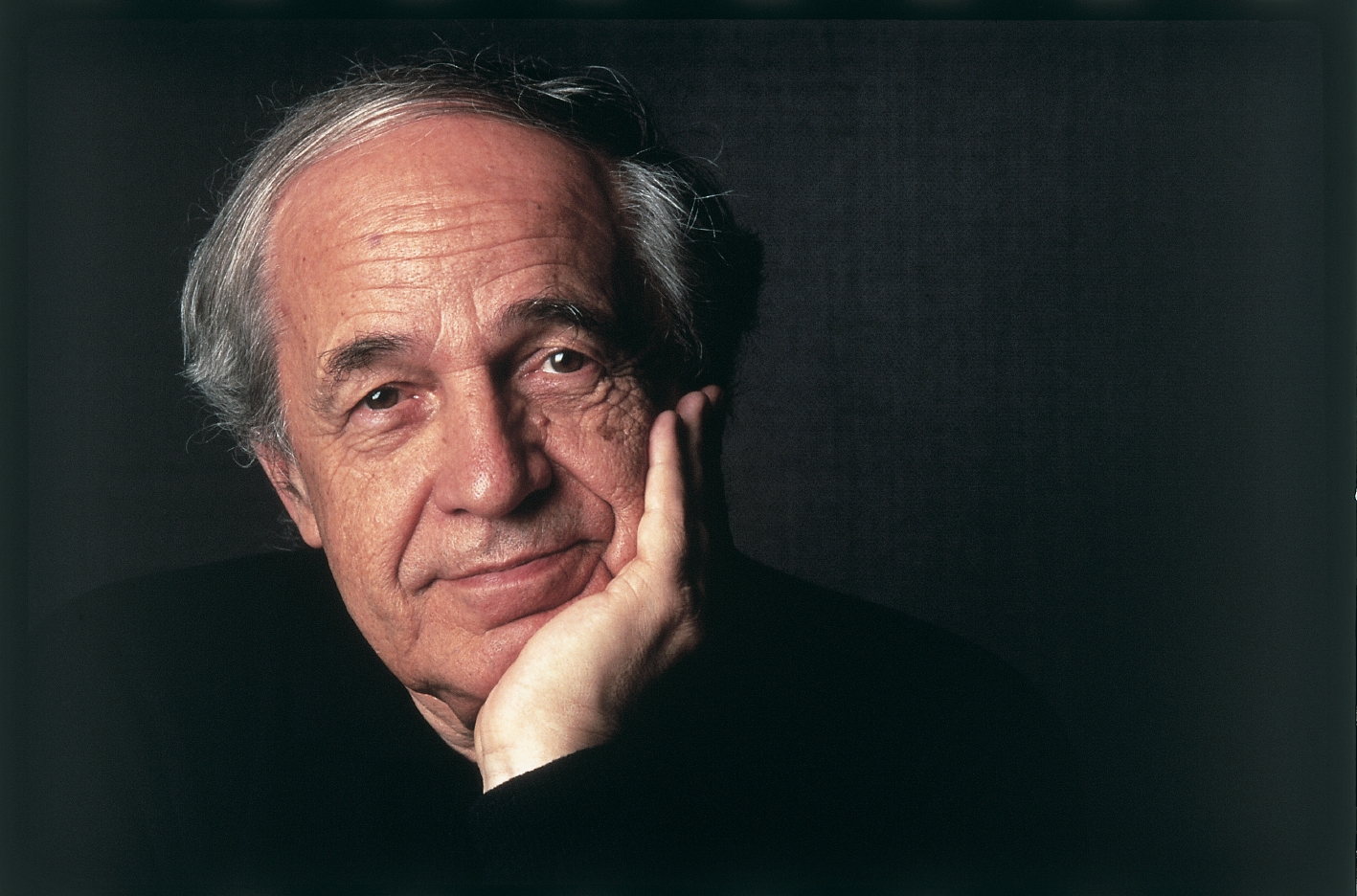

Dedicated with admiration and gratitude to Pierre Boulez and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

Live Concert Performance: Pierre Boulez conducting the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Movement #1

Live Concert Performance: Pierre Boulez conducting the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Movement #3

This work is available on

AUGUSTA READ THOMAS - SELECTED WORKS FOR ORCHESTRA.

This work is available on

AUGUSTA READ THOMAS "...Words of the Sea...".

Words of the Sea runs from 0-51-1:40

MOVEMENTS SHOULD BE LISTED IN THE CONCERT PROGRAM IN THIS WAY:

WORDS OF THE SEA (1995) Augusta Read Thomas (1964 -)

I. ...words of the sea...

II. ...the ever-hooded, tragic-gestured sea...

III. ...beyond the genius of the sea...

IV. ...mountainous atmospheres of sky and sea... (Homage to Debussy)

The four movements of Words of the Sea for orchestra are diverse and distinct, each undertaking to deal with the evocations prompted by a particular poetic phrase by poet Wallace Stevens. Despite their variety and distinctiveness, in fleeting whispers or proclamations, the four movements/scenes/poetic phrases reminisce about and relate to one another, resulting in a labyrinth of deeply interdependent connections.

The work is written to feature many of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra principal players through a series of brief solos as well as by intricate orchestration which results in distinct concertino groups momentarily rising to the foreground. The composition is dedicated with admiration and gratitude to Pierre Boulez and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra who presented the world premiere, and world premiere commercial recording, in 1996.

Wallace Stevens poem prompted and nurtured this music by alluring Thomas to see and imagine the sound of “words of the sea”, to appreciate an ocean's “ever-hooded tragic-gestured” nature, to imagine vast “mountainous atmospheres of sky and sea” and to contemplate what may be “beyond the genius of the sea”.

Thomas said, “I yearn to reflect in my own singing/composing the ways that listening has changed me. I write music that craves a listener - whomever that listener may be - and I am concerned with speaking honestly. What I say musically is prompted by a spirit of generosity.”

Some Sublimes:

Notes on Water, Weather, and Words in Augusta Read Thomas's ...words of the sea...

By Seth Brodsky

1

"Sublime" should be the wrong word. Do we need another shot of the lonely human, standing speck-like on the shore, sandwiched by endless sea and sky? This sublime is too big, too overstuffed. How about a more sinewy sublime, streamlined to the roots: sub, "up to", and limis, "the limit". In less than a minute, the first movement of Augusta Read Thomas's 1996 orchestral work ...words of the sea... plays out this kind of sublime. It goes up to a limit three times, and then past it. Though it's not in much use today, "sublime" can work as a verb. It's useful here: this movement sublimes.

First limit: "Majestic and intense". A fortissimo oboe punctures the silence and carves a lean icon into the air. It hangs above the orchestra, implores, and other solos call back reflex-like — trumpet, clarinets, flute, harp, violin, collecting the oboe line into harmonic pools. The sound hollows into a naked tritone for solo strings, bowed "bell-like", fusing into a fast crescendo for the whole 60-string body. The music hits an early tension-point, and breaks out: second limit. Tempo doubles, texture turns angular, "sharp, tight, percussive, machine-like". Speedy elastic lines veer between gaunt attacking chords. The whole orchestra is awake now; it thrums with grand exactitude, a kind of big dance taking up the whole floor. Everything melds for a moment; momentum slows, all the colors dam up and threaten to overflow. Third limit: the tempo lunges ahead yet again, the acoustic balloons as horns, trumpets, and trombones lock together. A single arching brass body, it torques and flips impossibly, like one Frank Gehry's silver-plated fish-buildings. This loudness feels giant, but also light and clear, full of space. The orchestra ricochets in blocks around it. Again, there is vast melding; everything roils in elegant noisiness.

Zero to this in 60 seconds. How did things get so big so fast, so instant-sublime? "Out of nothing to have come upon major weather", Wallace Stevens imagines. His poem "The Idea of Order at Key West" is the inspiration for Thomas's score. But this line comes from a later verse, "Notes Towards a Supreme Fiction". He makes a similar point in both poems: art sublimes. Supreme fiction wants to take it to the limit and past; that's what it does. He doesn't really explain how to come upon major weather. The point is simply that it happens, so be ready:

It is possible, possible, possible. It must

Be possible.

2

Well, how do you come upon major weather? If you're Wallace Stevens, you stand outside and take note. In so many poems made out of meteorological metaphors, Stevens plays the barometer, staking out the next occluded front. His words oscillate acutely to external conditions — "As if the air, the midday air, was swarming / With metaphysical changes...", he writes in Esthétique du mal. This answers the next question: what do you do when you come upon major weather? You record it, keenly, with a poem.

For Thomas in ...words of the sea..., the major weather is Stevens himself, and his 1934 poem "The Idea of Order at Key West". The emergent musical work couldn't be called a tone poem. Nothing is mimicked, no story is told. Thomas prefaces her four movements with phrases from the poem, but she imagines them only as abstract "scenes", each "diverse and distinct", each "undertaking to paint the 'picture' of the particular Wallace Stevens fragment."

"To paint", though, is one of music's notorious trap-door verbs. I won't disagree with Thomas, but I'll add to her. ...words of the sea... does more than paint a picture of a poem. It collapses a six-decade distance between two works in two mediums, into a hyperactive dialogue, unapologetically complex. To get past the chafe of old text-music debates, you need new metaphors of interaction. You could imagine, for instance, that Thomas's orchestra is a sonic map of Stevens's landscape. It surveys and traces all the poem's images; re-assigns them as emphatic timbres; projects an intimate soliloquy into a vast territory of instruments, 80-person-plus. Or perhaps the score is a kind of moldable mesh. The composer restlessly tills her unwritten music through 56 lines of visionary words; she catches some, lets others go, lets her growing composition to get splendidly bent out of one shape and into another. In the end, we hear a work made by a poem, in which the poem itself resides nowhere. And so on; anything but a trim and tidy setting-of-text.

It's hard, though, to beat the weather-metaphor. As much as anything, the 17 loaded minutes of ...words of the sea... constitute a wildly active barometer. In Thomas's characteristically euphoric mode, it records the rare, modulating climate of Stevens's text.

3

And, as title suggests, it's not really a text about the weather — or if it is, then (as Harold Bloom once quipped) "readers deeply moved by Stevens might have to murmur that never has so much been made out of the weather." The poet-among-the-elements scenario in "The Idea of Order at Key West" is plain. Stevens and a friend walk along the Key West shore and hear a girl singing to herself. But Stevens give the old nature-hymn a twist: the girl sings, but nature doesn't sing back. Shore + lonely human ≠ sublime. Singer and sea come close, but remain estranged. "The sea was not a mask. No more was she.", Stevens maintains. "The song and water were not medleyed sound..."

Among other things, Stevens clinches the essential contradiction of the barometer-poet: no weather, not even major weather, demands to be measured. No temperature asks to be taken, the air could care less. And the sea has no words, really. The poet, caught in major weather, measures for herself alone. "There never was a world for her / Except the one she sang and, singing, made." Hence the full Stevens line, which Thomas leaves strategically unsaid through her title's ellipses. Not "...words of the sea...", but "The maker's rage to order words of the sea..."

As the cliché goes, what Thomas leaves unsaid, she makes into music. More than paeans to skies and shores, her brief sound-pictures are records of enraged making. Their barometer gauges experiences of self, as inspired by environment as it is free of it. The title of the second movement, "...the ever-hooded, tragic-gestured sea...", initially seems to literally direct its sound-world. The opening solo, for the rare contrabass clarinet, is dark, inscrutable, and yes, ever-hooded. With painstaking slowness, other instruments creep out of the abysmal silence, only to cower under a fierce, steely outburst for brass and eventually full orchestra. The eruption has an oceanic size, but the tone of something more animate. This music swells as if stung, as if shot through with nerves, strained muscles, fear. Here again, Thomas's ellipses intentionally veil a larger epiphany in Stevens's poem:

For she was the maker of the song she sang.

The ever-hooded, tragic-gestured sea

Was merely a place by which she walked to sing.

The third movement motors jaggedly, it direction "with relentless energy", its tempo an unbroken Presto of spiked rhythms and bursts. "...beyond the genius of the sea..." is Thomas's chosen fragment here, and it speaks to the music's hungry driven-ness. But the movement, harmonically bare and nearly devoid of melody, feeds on another pleasure too. All incessant attacks and stamped-out blocks, it feels like a paragraph composed of entirely punctuations, parsing, plotting, emphasizing. In this it enacts a third essay in Stevens's "blessed rage for order", and tacitly cites an image near the poem's end, when electric lights

Mastered the night and portioned out the sea,

Fixing emblazoned zones and fiery poles,

Arranging, deepening, enchanting night.

4

"How does one stand / To behold the sublime...?". The biting question opens a little Stevens verse called "The American Sublime". With covert desperation, he goes on to pick apart and streamline the old sublime. Sure, stand at the shore like Friedrich's monk and wait for revelation. But, really, what is one waiting for? "But how does one feel?"

One grows used to the weather,

The landscape and that;

And the sublime comes down

To the spirit itself,

The spirit and space,

The empty spirit

In vacant space.

Fascinated, doubtful, Stevens can't stand at seaside with an open maw. So he issues an alt-sublime: Do not wait — make. Thomas shares Stevens's brand of skeptical sublime, and her score works Stevens's precept. ...words of the sea... is incapable of wide-eyed waiting. Everything must be made articulate, clenched by the pen and ardently laid out. Only in the fourth and last movement does Thomas permit herself anything like a scene of relaxation. Here the tempo is slow and pulmonary, the direction "Spacious and elegant". Diaphanous, harmonically packed chords ripple into each other, breathing in long, careful periods. The music shucks its first-movement fish-body, also abandons the stung nerves and "fiery poles" of the middle movements. Now, finally, it floats, "spirit and space".

But not "empty spirit in vacant space." There are all sorts of ghosts roaming about here. "Whose spirit is this?", asks Stevens in "Key West", since he knows "It was the spirit that we sought and knew / That we should ask this often as she sang." Here, the movement claims to sing of "...mountainous atmospheres of sky and sea..." But the music reveals another, human object of homage, Claude Debussy, whose La Mer is inevitably invoked by the movement's dedication. There's another ghost here too, one less seduced by the sea than the psyche, Alban Berg. His music submits this movement to a real haunting. It becomes an uncanny plot of paraphrases related by love and melancholy — Alwa's brassy erotic flare-up in Act II of Lulu, Berg's breathless glimpse of his mistress in the second movement of his Lyric Suite. But the spookiest, most enchanted allusion seems to be to the last of Berg's early Altenberg-Lieder. As Thomas's music filters itself into silence, tapping and tapering, it barely suppresses the text of Berg's song. It is, surprise, also a text about major weather: "Here is Peace. / Here I can weep my fill about everything...Here is Peace! Here the snow falls gently into / flowing water."

Here, too, Thomas's cycle of sea-pictures absorbs all its texts at once, even as it reaches its own limit. This seems to be the mode of an alt-sublime: go up to the limit, overtake it, bring it back in. Stevens's singer absorbs the ocean with her song, Berg's singer absorbs the world with her tears, and Thomas absorbs them both with her own permeable singing. Sublimes, even alt-sublimes, are uncomfortable modes today. They may strike more sinewy postures, but they can't get past an Ur-instinct for too-big-ness. How to avoid looking silly in front of the sublime, Stevens wants to know. "What wine does one drink? / What bread does one eat?", he asks, almost petulantly. ...words of the sea... replies: eat other poems, other music.

— Seth Brodsky

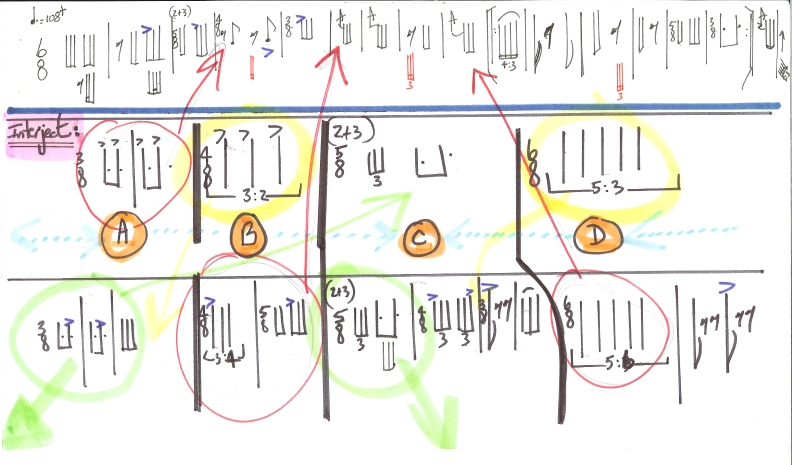

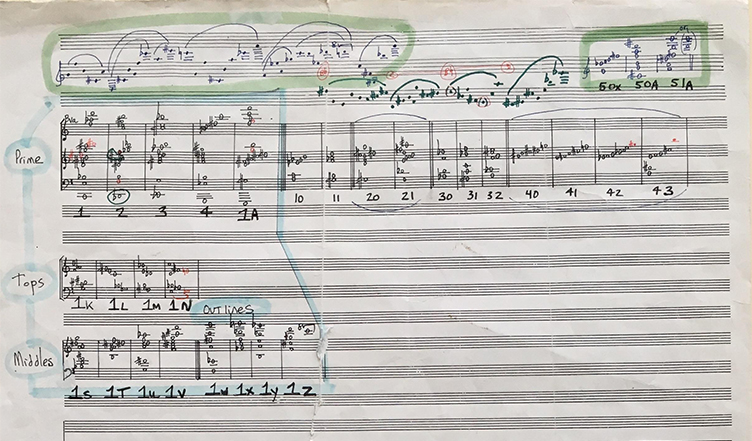

To purchase a Sketch of words of the sea, please visit the Online Store.

The Idea of Order at Key West

By Wallace Stevens

The sea was not a mask. No more was she.

The song and water were not medleyed sound

Even if what she sang was what she heard,

Since what she sang was uttered word by word.

It may be that in all her phrases stirred

The grinding water and the gasping wind;

But it was she and not the sea we heard.

For she was the maker of the song she sang.

The ever-hooded, tragic-gestured sea

Was merely a place by which she walked to sing.

Whose spirit is this? we said, because we knew

It was the spirit that we sought and knew

That we should ask this often as she sang.

If it was only the dark voice of the sea

That rose, or even colored by many waves;

If it was only the outer voice of sky

And cloud, of the sunken coral water-walled,

However clear, it would have been deep air,

The heaving speech of air, a summer sound

Repeated in a summer without end

And sound alone. But it was more than that,

More even than her voice, and ours, among

The meaningless plungings of water and the wind,

Theatrical distances, bronze shadows heaped

On high horizons, mountainous atmospheres

Of sky and sea.

It was her voice that made

The sky acutest at its vanishing.

She measured to the hour its solitude.

She was the single artificer of the world

In which she sang. And when she sang, the sea,

Whatever self it had, became the self

That was her song, for she was the maker. Then we,

As we beheld her striding there alone,

Knew that there never was a world for her

Except the one she sang and, singing, made.

Ramon Fernandez, tell me, if you know,

Why, when the singing ended and we turned

Toward the town, tell why the glassy lights,

The lights in the fishing boats at anchor there,

As the night descended, tilting in the air,

Mastered the night and portioned out the sea,

Fixing emblazoned zones and fiery poles,

Arranging, deepening, enchanting night.

Oh! Blessed rage for order, pale Ramon,

The maker's rage to order words of the sea,

Words of the fragrant portals, dimly-starred,

And of ourselves and of our origins,

In ghostlier demarcations, keener sounds.

John von Rhein, Chicago Tribune September 19, 2004 "Thomas’ music, particularly her orchestral music, fairly explodes with an extroverted boldness of utterance audiences and musicians alike find challenging yet immediate. It’s music that doesn’t sound like anybody else’s – music that insists you pay attention. Thomas’s disk…is packed with inventive ideas, poetic imagery and fresh sonorities. “…words of the sea…”, a suite of four seascapes inspired by a Wallace Stevens poem, creates a mysterious atmosphere of vast space, shimmering surfaces, distant thunder and dramatic events. Melodies are angular, rhythms complex, textures transparent, dynamic contrasts bold."

Lawrence Johnson, Gramophone Classical Music Magazine Awards Issue Autumn 2004

Headline: Oceanic impressions from a singular voice who shows a real flair for orchestration

"Thomas’s high sustained string lines [in WORDS OF THE SEA] match Stevens’ graceful and metaphysical angst. She has a singular voice and a real flair for orchestration, as with the see-sawing string lines that hand, questioning, in the air against shimmering percussion. The playing of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra is first class and Pierre Boulez obtains a clarity and expressive point."

Andrew Pincus, The Berkshire Eagle Autumn 2004 "WORDS OF THE SEA is like a short symphony. The piece is arresting in its play of colors and moods. In the slow finale of WORDS OF THE SEA she (the sea) is a force. The mystery of that movement echoes the mystery at the end of Stevens’ poem, in which the songs of the singer and ocean are destined to remain separate."

Christopher Ballantine, International Record Review, October 2004

"American-born Augusta Read Thomas, now 40, is currently composer-in-residence with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra — a position she has held since 1997 and will vacate in 2006. Working in a late-Modernist idiom — Berio is one of her models, and it's not insignificant that Pierre Boulez is her conductor here — she has won a string of awards and been the recipient of an impressive number of commissions from orchestras and other bodies in the USA and Europe.

"The earlier of the two works on offer, ...words of the Sea..., appears in a recording made at its première in 1996, with the Chicago orchestra at its brilliant best. The 17-minute piece is closely linked to a 1934 poem by Wallace Stevens, The idea of order at Key West. Walking on the seashore, the poet and a friend encounter a girl singing to herself. He is struck by a profound paradox:

"She was the single artificer of the world

in which she sang. And when she sang, the sea,

Whatever self it had, became the self

That was her song, for she was the maker."

"Thomas' work does not set out to depict this scene so much as to reflect upon some of its aspects: it's a purely orchestral piece with, however, each of its four movements prefaced by a small fragment from the poem. The first, "....words of the sea...." is a wonderful example both of Thomas' way of suffusing her late-Modernist idiom with vivid melody, and of a style that is taut, chiselled, lucid, glowing with colour and energy. In the second movement, "...the ever-hooded, tragic-gestured sea...", Thomas summons up the deep, dark, unfathomable sonorities of the contrabass clarinet, along with slow, heavy orchestral surges and an outburst of frightening but majestic power. The third returns us to the image of the girl singing "...beyond the genius of the sea...": it's a movement of mad, frolicking exuberance, whose dancing, darting melodic line seems to collide constantly, synergetically, with some overwhelming force. The final movement is the calmer, more meditative "...mountainous atmospheres of sky and sea...", its' great swathes of colour and slow rates of change evoking spaces of vast dimension. Though the movement is offered as a tribute to Debussy, the sound qualities are closer to Alban Berg than to the composer of La Mer.

"The other work on the disc is In My Sky at Twilight, a chamber-like piece that was premièred just two years ago. Boulez conducts it here in a blazing, virtuosic performance by the 18-piece Chicago MusicNOW Ensemble and soprano Christine Brandes. It's a passionate, ecstatic, tragic composition on the topic of love. Thomas has picked, excerpted and seamlessly strung together 16 poetic fragments, representative of three different millennia and many different parts of the globe. They include an anonymous love lyric from Ancient Egypt, Sappho and Pindar from Ancient Greece, a poet from ninth-century Japan, Gerard Manley Hopkins and other from nineteenth-century England, and Pablo Neruda and e.e. cummings from the twentieth century. These are grouped to make two contrasting narratives — a perfervid movement flushed with sensuous love, and a quieter second movement dealing with loss and mourning but also, very movingly, with love that survives the scythe of death. So a particular dimension of human experience is at once universalized in the chosen excerpts, personalized in the single soprano's intense subjectivity, and rendered audible in her heightened, phatic vocalizing as well as in the rich sonic sonority imagery of the orchestral score. The work needs a soprano of consummate ability — and it has one. Brandes is quite wonderful, singing almost continuously through the work's 19-minute duration, and doing so with warmth, power, precision and fine control of vocal timbre. There are surely few of her generation with greater skill, or with superior mastery of her elected idiom."

Donald Rosenberg, Cleveland Plain Dealer "Words of the Sea [is] a vibrant series of aquatic images that had no difficulty standing alongside favorite pieces by Barber and Prokofiev. Words of the Sea is a healthy example of a work from a composer who is smitten with the chameleonlike qualities of the orchestra and knows how to exploit its myriad facets."

To obtain examination or performance material for any of

Augusta Read Thomas's works, please contact G. Schirmer Inc..